My Logos-generated Bible reading schedule does some odd things at times. Yesterday, I was scheduled to read Acts 2:1–42 (42 verses) followed by verses 43–47 today (5 verses). What’s up with that? So since yesterday was Saturday and I had some extra time, I decided to read all of chapter 2 and get ahead a little bit in my reading schedule. But this is a good thing, because Acts 2 really should be taken as a whole unit. Peter preaches to the crowd, recounting David’s Messianic prophecies in the Psalms, with the entire message coming to a climax in 2:37–38: “Those who heard this were pierced [κατανύσσομαι katanyssomai /kah-tah-NOOSE-ȯ-my/] to the heart and said to Peter and the rest of the apostles, ‘What shall we do, Men of the Brothers?’ And Peter to them, ‘Repent!’ [saying] ‘And let each one of you who does [italics my gloss] be immersed upon the name of Jesus Messiah into the forgiveness of your sins, and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.'”

Now I have already dealt with Acts 2:38, specifically the phrase “into the forgiveness of your sins” (click link in verse above), but I want to deal with the results of that call to repentance. In Acts 2:41, we learn that over 3000 were added to the number of Christ-followers on that day. Verse 42 is my focus today: ἦσαν δὲ προσκαρτεροῦντες τῇ διδαχῇ τῶν ἀποστόλων καὶ τῇ κοινωνίᾳ, τῇ κλάσει τοῦ ἄρτου καὶ ταῖς προσευχαῖς (ēsan de proskarterountes tē didachē tōn apostolōn kai tē koinōvia, tē klasei tou artou kai tais proseuchais, ‘And they devoted themselves to the apostles’s teaching and to the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to the prayers’). This is how the verse appears in most modern Greek texts of the New Testament and subsequently translated into most English versions.

Much Ado about a Comma

You may have noticed that in the verse, I highlighted the comma after the word κοινωνίᾳ. I can hear you now: “Come on, Scott! A comma? Really? Give me some filet mignon I can savor, not a dinky little baby-carrot comma!” But fasten your seatbelts, because the presence or absence of this comma has a huge impact on how this verse is understood. A few years ago, I presented a paper in a professional conference on this verse, and my personal joke is that it was my 25-page paper about a comma. Read on and see why this comma is so important (and no, I’m not reproducing the entire 25-page paper here!).

First of all, I must say that the original manuscripts of Scripture did not have punctuation as we know it today. Not only did they not have punctuation, they did not have spaces between words, either. Just look at an image of the Rosetta Stone to see what I mean. So how does a comma (or any punctuation, for that matter) end up in today’s versions of the Greek New Testament (GNT)? Because the modern-day editors of the GNT put it there in an effort to help translators see the presumed syntax of the text.

But a good translator knows that the placement of a punctuation mark in the Greek text can be just as interpretive as how one translates a particular Greek word into English (or into whatever receptor language). As such, there are a couple reasons to question this comma here. The first reason is that in the history of the transmission of the text, someone decided that καί (kai ‘and’) needed to be inserted in that spot at some point. The variant is not well attested, but it did make it into the textus receptus, the Greek manuscript that has been the foundation for all versions of the King James Bible. Thus, the KJV renders the middle part of the passage: “and fellowship, and in breaking of bread.” Modern eclectic texts do not have the καί, but replace it with the comma. The 3rd edition of the UBS GNT does not even reference the variant reading.

The second reason to question the comma is that it is possible to make a sensible translation of the verse without it, if the translator does his or her homework. I have done that homework, and I present to you here my understanding of Acts 2:42. To be fair, I will offer four possibilities of translation, but my study leads me to believe that one of the last two possibilities is more probable, with Option 4 being my personal preference.

Four Possible Translations

1. Four individual manifestations, reflecting an implied or variant medial καί, with each dative case noun functioning as a direct object of the main verb:

| “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching, and to the fellowship, and to the breaking of the bread, and to the prayers;” or |

| “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship [i.e., apostles’ modifies both teaching and fellowship, which seems to be the gist of the KJV translation], and to the breaking of the bread, and to the prayers.” |

2. Two complementary pairs of manifestations, rejecting the implied or extant medial καί and acknowledging Luke intended a comma break between the two pairs:

| “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to the fellowship, to the breaking of the bread and to the prayers.” |

3. Two manifestations, with the second (“fellowship”) qualified by the following couplet (double appositive, explains lack of καί, no comma necessary in Greek text):

| “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to the fellowship, [which includes] the breaking of the bread and the prayers” (see 1 Corinthians 10:16). |

4. Three individual manifestations (lack of καί before “breaking of bread”):

| “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching, [and] to the fellowship of/participation in the breaking of the bread, and to the prayers” (again, see 1 Corinthians 10:16; because we have the serial comma in English, we wouldn’t need to translate the first καί). |

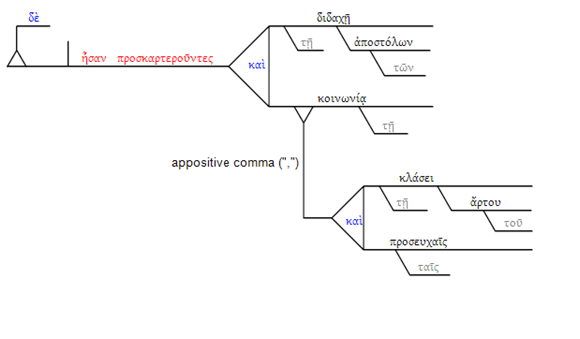

Four Sentence Diagrams

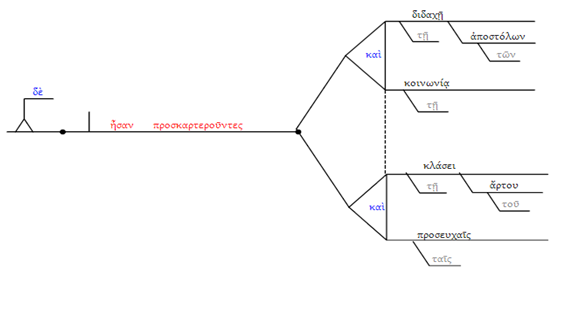

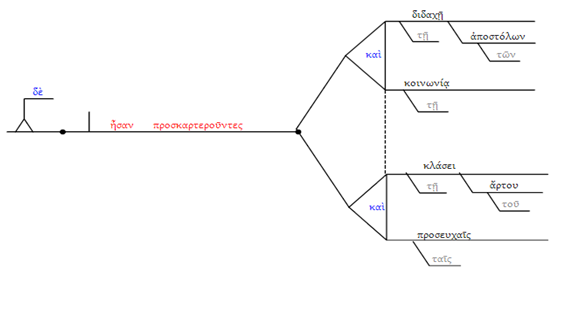

Anybody remember sentence diagramming from junior high English? How fun was that, right? Well, for my part, I’m glad I half-way paid attention to that, because it comes in quite handy in this analysis. I hope my English teachers approve. Note Figures 1 through 4 below. [NOTE TO READERS: If for whatever reason you don’t see the diagrams, please let me know. They show up in my browser (IE9), but I’m not sure how they’d work in other browsers.]

Figure 1: Sentence Diagram for Options 1 and 2: Acts 2:42.

Two pairs separated by a comma (Option One; as in the USB 4th Edition), or, if the variant reading with καί is accepted (textus receptus), four individual manifestations of their devotion (Option Two).

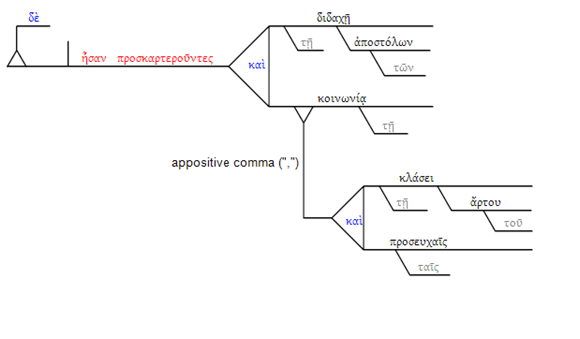

Figure 2: Sentence diagram for Option 3: Acts 2:42

The first or both of the latter two dative nouns are in an appositive relationship to κοινωνίᾳ. No comma is necessary.

Figure 3: Sentence diagram for Option 4: Acts 2:42

Three manifestations of the believers’ devotion, with τῇ κλάσει in a genitive relationship to τῇ κοινωνίᾳ; or alternately, with τῇ κλάσει as the direct object of the verbal action of τῇ κοινωνίᾳ, that is, “the sharing/participation in the breaking of bread.” See 1 Corinthians 10:16 for support for this latter option. Accepting either reading would mean neither the Greek nor English texts should have a comma after τῇ κοινωνίᾳ/”fellowship.”

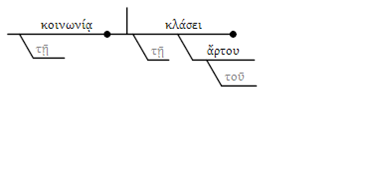

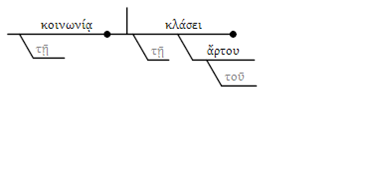

Figure 4: Partial sentence diagram for the translation “participation in the breaking of the bread”: Acts 2:42

The alternate reading would look like this (akin to 1 Corinthians 10:16), with κλάσει as the dative case direct object of the verbal action of κοινωνίᾳ:

Option 4 actually follows the Vulgate (Latin) translation, which has “the breaking of the bread” in genitive case (case of possession) rather than in dative case (object case), as in Greek. But if the two nouns are essentially the same thing, they can take the same case in Greek even if they have a genitive relationship. This actually seems quite common in the opening chapters of Acts, especially in the phrase ἄνδρες Ἰουδαῖοι/Ἰσραηλῖται/ἀδελφοί (andres Ioudaioi/Israēlitai/adelphoi, ‘men of Judah/Israel/brothers’): ἄνδρες is nominative/vocative plural, as is the relational noun. Alternately, the phrase could be translated “fellow Judeans, Israelites, brothers [and sisters].”

And All This to Say What?

The point of this whole study was really to find out just what κοινωνίᾳ (koinōnia ‘fellowship’) embraced in the early church. I believe the reference to “the breaking of the bread,” because both nouns have the definite article in Greek, is more specific than just a general meal. I believe the reference is to the Last Supper (the Lord’s Table, my preferred term for “communion”), where Jesus commanded his disciples to “do this in remembrance of me.” So fellowship is not just a potluck or a gathering of believers for whatever purpose, but as 1 Corinthians 10:16 says, a “participation [κοινωνίᾳ] in the body and blood of Christ.”

Those of us in the Restoration Movement (Christian Churches/Churches of Christ) as well as the Catholic Christ-followers instinctively understand the centrality of participating in communion/the Lord’s Table/Eucharist on a weekly basis, even if we have differing theologies about the elements. If there are other denominations or congregations out there that practice a weekly as opposed to an erstwhile communion, they are to be commended for showing the same devotion to this “fellowship” as the early Christ-followers.

So whenever you partake of the Lord’s Table, remember that the elements are not just bread and juice, but an intimate connection to the sacrifice of Jesus and a sharing with one another, regardless of denominational background, in the historical events that should be foundational to all Christ-followers, the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus.

Peace!